Psychological Theory

Organisational Competency One: Knowledge of the DisciplineOrganisational Psychologists are required to demonstrate facility with a broad understanding of psychological theory as it relates to the successful functioning of organisations. Below are some examples of theories used in everyday practice.

Conservation of Resources Theory (COR)

Conservation Of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1989), was designed to help explain stress. The theory suggests people are motivated to keep and protect their resources and to use their resources to gain further resources. There are ‘object resources’, like a car or a house, ‘condition resources’, such as employment and marriage, ‘personal resources’, like skills and personal traits like self-esteem, and ‘energy resources’, like credit, knowledge, and money.

Psychological Stress happens when there is a threat of a loss of resources, an actual loss of resources, or a lack of gained resources following the spending of resources (e.g. sowing a field with a crop, but having that crop fail).

COR comes with three ‘principles’.

Principle 1: The primacy of resource loss. This means people do not like to lose a resource - and that the loss of a resources is a more impactful experience for people than a gain of the same amount. E.g. it’s more impactful to lose $10,000 than to get a raise of the same amount.

Principle 2: Resource investment. That is, people must invest resources to protect against resource loss, recover from losses and to gain resources. For example, an employee might be willing to invest some extra time at work each day in exchange for a shortened work week.

Principle 3: Resource gain increases in salience when resource loss has been high or chronic. Sounds complex, but it simply means that while resource gains may have little impact on people who are not experiencing loss, these same gains become very impactful when major or ongoing resource loss has been experienced. E.g. a person who has lost their job will be extra grateful for even a relatively small tax return.

Example:

COR has been used when studying work/family stress, burnout and general stress. In work/family stress, for example, COR research has studied how the distribution of a person’s resources have affected their home life, with some research finding that putting too much of one’s resources into one’s work may lead to family problems at home.

Hobfoll, Stevan (1989). "Conservation of Resources. A New attempt at conceptualizing stress". The American Psychologist. 44 (3): 513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

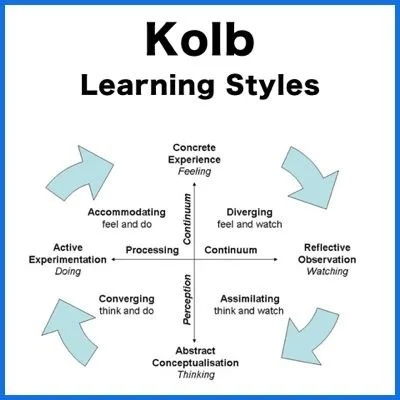

Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT)

David Kolb defined Experiential Learning as:

“the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combinations of grasping and transforming the experience.” (1984)

Image source: https://mihirvalerablog.wordpress.com/

The process as described by Kolb involves four stages: Concrete experience (the learner encounters a new experience), Reflective observation (the learner reflects on the experience), Abstract conceptualisation (as a result of reflection, the learner forms new ideas, or makes changes to existing ideas) and Active experimentation (the learner applies the new ideas… an experience that can become the Concrete experience for a learning new cycle). It is a cyclical process in which all four of these bases are touched upon for deep learning to occur.

Example:

One simple use of this is, at the end of a session, to asking an executive coaching client to summarise their learning from a discussion we’ve had – e.g. ‘What has been most useful for you from that discussion?’ This invites the client to engage in Reflective observation as they recall what we spoke about, and in Abstract conceptualisation as they express what was learned. A follow up question ‘What difference does that make for next time you encounter X situation?’ invites active experimentation with what was learned.

Reference

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

PERMA Wellbeing Theory

Prof Martin Seligman’s 'PERMA Wellbeing Theory’ (Seligman, 2012), draws together five elements of psychological wellbeing. Seligman makes the case that these elements can help people reach a life of fulfilment, happiness, and meaning - and, importantly for an organisational context - he contends that this model can be applied to individuals, teams and whole systems. He does not say that we each need all of these elements of wellbeing to be happy, but draws out attention to the fact that we can intentionally boost one or more areas if we so desire as part of a wholistic wellbeing plan.

The five elements are:

Positive Emotions - feelings of happiness, joy, fulfilment, peace. That is, the experience of these emotions themselves can be beneficial.

Engagement - sometimes called ‘psychological flow’ or ‘being in the zone’, this refers to a state of being perfectly challenged for our skill level. Not too easy (which leads to boredom) and not too hard (which may cause stress or just disengagement). Note, this is a moving target as we grow in skill.

Relationships - feeling connected, respected; having positive, constructive interactions with colleagues, management, and clients. Having good quality relationships consistently rate highest among the five elements of PERMA in terms of outcomes for individual and organisational wellbeing.

Meaning - beyond the bottom line, or individual gain, this element is about serving a bigger purpose, whether that purpose is a cause such as tackling climate change, or ensuring that the poorest of the poor have some opportunity to access the services provided by the organisation - or an ideal. Importantly, this meaning cannot be imposed externally through mandates and policy requirements. Meaning needs to tap ‘intrinsic motivation’ by being invitational, inspirational or by being elicited from individuals.

Achievement - a sense of satisfaction gained in striving toward - and perhaps even accomplishing - a goal.

Example

PERMA has been used in undertaking an organisational wellbeing audit; with the elements of PERMA used as the underlying structure for a wellbeing survey or other needs analysis. This is often with the addition of an ‘H’ for physical Health (nutrition, sleep & exercise), to make ‘PERMAH’.

Reference

Seligman, M.E., Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. 2012: Simon and Schuster.

The SCARF Model

The SCARF Model (Rock, 2008), states that much of our social behaviour is driven by both minimising threat and maximising reward. Secondly, it also states that several areas of social experience draw upon the same brain networks used for primary survival. In other words, social needs are treated in a similar way in the brain as the basic needs for, say, food and water. Thus situations in which collaboration is needed, such as most workplaces - can create a very potent threat or reward response. Knowing this, we can intentionally seek to minimise threats and choose meaningful rewards to potentially improve wellbeing, motivation, and productivity.

The SCARF model describes five areas of human social experience:

Status, which is about relative importance to others. Certainty, which concerns being able to know what is coming in future. Autonomy, which provides a sense of choice, or control over events. Relatedness or connection, which is a sense of safety with others, a sense of ‘friend’ rather than ‘foe’. And finally, Fairness - which is the perception of fair exchanges between people.

These five areas activate either the neural ‘primary reward’ or ‘primary threat’ circuitry of the brain.

Example:

Knowing that a lack of autonomy activates a genuine threat response, a leader may choose consciously avoid micromanaging their employees. Alternatively, a line manager might grant more autonomy as a reward for good performance - a reward that in many situations may be a more meaningful motivation for an employee, then say, a raise.

Reference

Rock, D. (2008). SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others. NeuroLeadership journal, 1(1), 44-52.